來源:中國日報網

近日火爆全球的現象級韓劇《魷魚遊戲》引發了觀看熱潮,帶火了周邊產品的銷售,也曝光了韓國普遍存在的債務危機。過去幾年來,韓國平民負債率不斷攀升,貧富差距急劇擴大,許多人都是猝不及防就陷入了債務危機。

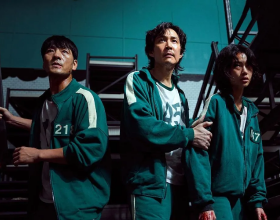

Squid Game, which was released on 17 September, is on track to become Netflix’s most-watched show ever. Photograph: Youngkyu Park/Netflix/AFP

After midnight, when the crowds of revellers have gone, Choi Young-soo crouches in a shabby alleyway in Seoul’s wealthy Gangnam district. This is the only time that the 35-year-old, a part-time food delivery rider, dare leave his tiny room at a cheap hostel he shares with about 30 other people.

午夜後,當狂歡的人群散去,35歲的兼職送餐員崔英秀(化名)蜷縮在首爾江南區(富人區)一條破敗的小巷裡。只有在這個時間崔英秀才敢離開自己和其他30人合住的那個超小的便宜旅店房間。

The rooms, he says, are “only slightly bigger than coffins”.

他說,房間“只比棺材稍微大一點”。

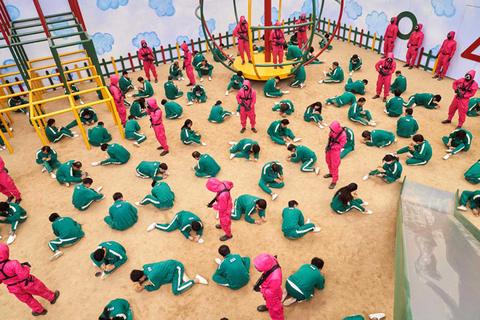

In a fictional world, Choi would not be out of place among the contestants on Squid Game, the wildly popular South Korean dystopian drama that pits the heavily indebted against each other in a macabre, blood-spattered race for an unimaginably large cash prize.

崔英秀的處境和爆款韓劇《魷魚遊戲》虛構世界中的那些玩家沒什麼不同。在這部反烏托邦韓劇中,負債累累的人為了鉅額獎金加入了一場互相殘殺的血腥遊戲。

But Choi’s desperate situation is real – he is one of a large and growing number of ordinary South Koreans who find themselves choked by debt, in a country where taking out a loan is as easy as buying a cup of coffee.

但是崔英秀的絕望處境是真實的,他是眾多債臺高築的韓國平民中的一員,而且這一人群還在不斷擴大。在韓國,借貸就和買杯咖啡一樣容易。

'I feel like other people sense that I’m a failure, so I only come out at night to smoke and watch the stray cats,” Choi says.

崔英秀說:“我覺得在其他人眼裡我就是個失敗者,所以我只有夜裡才出來抽抽菸,看看野貓。”

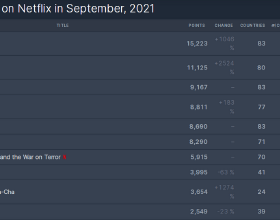

Squid Game, which was released on 17 September, is on track to become Netflix’s most-watched show ever, captivating viewers around the globe with its mixture of dark drama and commentary on the failures of South Korean-style capitalism.

9月17日上線的《魷魚遊戲》有望重新整理奈飛的收視紀錄,這部揭露韓國式資本主義地獄的暗黑劇俘獲了全球各地的觀眾。

Household debt in South Korea has risen in recent years and is now equivalent to more than 100% of GDP – a level not seen elsewhere in Asia.

近年來韓國家庭負債率一直在上升,目前已經超過國內生產總值的100%,這在亞洲其他地區都是沒有出現過的。

Indebtedness has gone hand in hand with a dramatically widening income gap, exacerbated by rising youth unemployment and property prices in big cities beyond the means of most ordinary workers.

伴隨著負債增多,韓國的收入差距也急劇擴大。與此同時,青年失業率的上升和普通勞動者難以企及的大城市房價進一步拉大了貧富差距。

As Squid Game illustrates, a sudden redundancy, a bad investment or simply a run of bad luck can force people to turn to high-risk lenders just to keep their heads above water.

正如《魷魚遊戲》所描述的,一次突如其來的裁員,一項失敗的投資,或者僅僅是一連串厄運,都可能迫使人們求助於高利貸以勉強度日。

The series’ popularity is proof that the misery of crushing debt is a universal experience but, according to Lee In-cheol, the chief executive of the thinktank Real Good Economic Research Institute, its Korean backdrop is far from coincidental.

這部韓劇的火爆證明,債臺高築的苦難是普遍存在的。但是,智囊機構真善經濟研究所的總裁李寅哲指出,韓國人陷入債務危機絕對不是偶然。

'The total amount of debt run up by ordinary South Koreans exceeds GDP by 5%,” he says. “In individual terms, it means that even if you saved every single penny you earned for an entire year, you would still be unable to repay your debt. And the number of people with debt problems is rising at an exponential rate.”

他說:“韓國平民的債務總額已經超出了國內生產總值的5%。從個人角度來看,這意味著即使你不吃不喝把一年掙的錢全部省下來,你也無法還清債務。而有債務問題的人口數量正在以指數級速度增長。”

In response, the country’s financial services commission and financial supervisory service recently resolved to prevent more South Koreans from falling into debt. “That is why major banks have acted to curb borrowing,” Lee said. “But is that really going to help people, especially in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic?”

為此,韓國金融服務委員會和金融監管服務局最近正致力於防止更多韓國人負債。李寅哲說:“這就是為什麼大銀行已採取限制貸款的措施。但此舉真的能幫助人們嗎?尤其是在新冠疫情期間?”

Squid Game, which was released on 17 September, is on track to become Netflix’s most-watched show ever. Photograph: Netflix/AFP

Like many of Squid Game’s 456 fictional contestants, who are invited to play Korean children’s games and risk their lives in the process for a 45.6bn won prize, Choi’s plunge into indebtedness came with alarming speed.

《魷魚遊戲》中456名虛構的玩家受邀來玩韓國兒童遊戲,冒著生命危險爭奪456億韓元(約合人民幣2.5億元)的大獎。同這些玩家一樣,崔英秀陷入負債也是猝不及防的。

Just two years ago, he was working as an IT engineer for a firm in Pangyo – South Korea’s answer to Silicon Valley. Years of punishing overtime and late nights took a toll on his health. After lengthy discussions and a year spent planning and saving, he and his wife decided to open a pub in their home town, Incheon.

就在兩年前,崔英秀還在板橋(韓國版矽谷)的一家公司做軟體工程師。多年的辛苦加班和熬夜壓垮了他的身體。他和妻子商量了很久並花一年時間進行規劃和儲蓄後,夫婦二人決定在老家仁川開一家酒館。

It was a decision they would regret, despite their modest ambitions. “We weren’t hoping to become millionaires,” he says. “We would have been satisfied with earning the same as before. All I really wanted was more sleep … even an extra hour a day.”

儘管他們要的不多,但這是一個會讓他們後悔的決定。崔英秀說:“我們不指望成為百萬富翁。我們只要掙得和以前一樣多就滿足了。我真正想要的是多睡一會兒,哪怕一天多睡一個小時也好。”

After an encouraging start, their business fell victim to the coronavirus pandemic. After bars and restaurants were ordered to close as early as 9pm to prevent the virus from spreading, the number of customers reduced to a trickle, then dried up altogether.

生意一開始不錯,但很快就受到了新冠疫情的打擊。為了防止病毒傳播,酒吧和餐廳被要求在晚上9點前關門,客源自此銳減,後來幾乎沒有了。

'Sometimes we didn’t have a single customer,” Choi says. “It was just the two of us, playing loud music to cheer ourselves up, even though we knew that would mean higher electricity bills. But we couldn’t switch it off.”

崔英秀說:“有時候我們一個客人也沒有。酒館裡只有我們兩個人,把音樂開得震天響,就為了讓自己好過一點,儘管我們知道這樣做會增加電費。但是我們就是沒法關掉音樂。”

After failing to pay their rent for four months, the couple knew they were testing their landlord’s patience and sought help. Securing a bank loan was surprisingly easy, but they were shocked to find the interest was a steep 4%.

在拖欠店鋪租金四個月後,這對夫婦知道房東也等不起了,於是就向銀行尋求幫助。沒想到貸款非常容易,但是他們震驚地發現利率高達4%。

Within months they had taken out loans from all five of South Korea’s high-street banks, using their home as collateral. Inevitably, they had to borrow more to pay off existing loans, joining long queues of troubled business owners eager to secure cash from commercial lenders at interest of more than 17%.

幾個月內,他們就用自己的房產做抵押借遍了全部五家韓國高街銀行。為了償還現有的貸款,他們不可避免地要向銀行借更多錢,最後他們跟其他深陷困境的企業主一樣,排隊申請利率超過17%的高息商業貸款。

'By then, I no longer cared about how high the interest rates were,” Choi says. “I was getting so many calls and text messages demanding that I repay my loans. It took over our lives. My wife said she even heard me muttering about interest rates in my sleep.”

崔英秀說:“那時候,我已經不在乎貸款利率有多高了。我每天都接到很多電話,收到很多簡訊,催我還貸。債務已經佔據了我們的生活。我的妻子說,她甚至聽到我在睡夢中唸叨利率。”

In a desperate attempt to pull themselves out of their downward spiral, Choi’s wife found a job at a restaurant in another part of the country, and the couple asked his parents to look after their two young children.

絕望中,為了擺脫這一惡性迴圈,崔英秀的妻子在韓國另一個地方找到了一份餐廳的工作,夫婦二人還拜託男方父母幫忙照顧兩個小孩。

Choi says he has heard a lot about Squid Game, but is unable to become part of the global frenzy that has helped the nine-episode show amass tens of millions of viewers.

崔英秀說,他經常聽說《魷魚遊戲》這部劇,但是無法成為全球追劇大軍中的一員。這部9集韓劇已經吸引了數千萬觀眾。

'You have to pay to watch it and I don’t know anyone who will let me use their Netflix account,” he says. “In any case, why would I want to watch a bunch of people with huge debts? I can just look in the mirror.”

崔英秀說:“這部劇必須付錢才能觀看,我也不認識能讓我借用奈飛賬戶的人。再說了,我幹嘛要看一堆負債累累的人?我自己照照鏡子就好了啊。”

英文來源:衛報

翻譯&編輯:丹妮